WILLIAMSBURG, Va. — On a crisp, sunny day a group of William & Mary law school students stands gazing at the 20x16-foot Hearth Memorial to the Enslaved found in the heart of campus. Curiously, they listen to the story behind the structure on a class tour, soaking in every word, relating it to their very existence as African American students among a predominately white campus population.

"Seeing this, it's kind of like a recognition. Sometimes Black students can feel a little invisible on campus. Stuff like this, it addresses it. You're not alone. There were people here before that built this campus, so don't worry, of course you belong," said Treyvon Jordan, who graduates from the law school in May.

Granite blocks resembling a West African weaving pattern adorn the brick structure. Each one represents an enslaved person who labored on campus and helped bolster the school's economy.

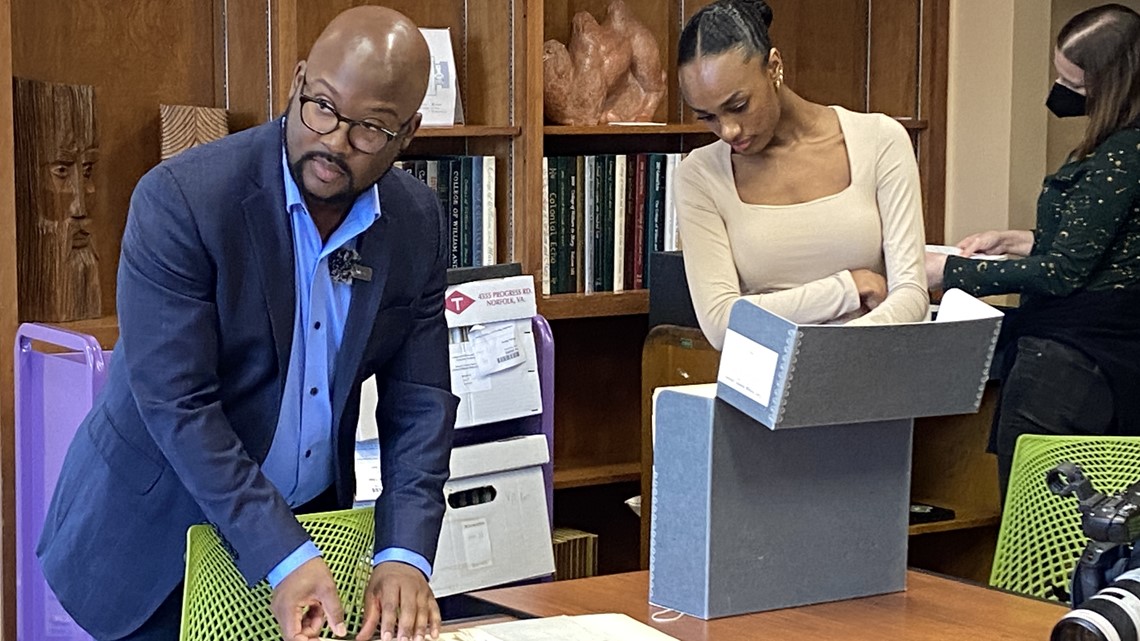

Research to uncover more names continues as part of the Lemon Project. Named after one of the enslaved persons, the Lemon Project is an endeavor by the University to rectify the horror of exploiting slave labor by building bridges between the campus and African American communities through student support, programs, and research.

Lemon was one of 30 enslaved persons brought to the campus in the 1780s. Researchers discovered he grew and sold produce to the college.

"Lemon is appearing from about 1789 to about 1814. We know he passes in 1817 -- so again -- we have expanded the narrative of his life," said Jajuan Johnson, a postdoctoral research associate for the Lemon Project.

Each time, researchers uncover a date associated with an enslaved person, the discovery is engraved onto the memorial, even if it means inscribing "unknown person." The goal is to connect each granite block with a story. So they dig in Special Collections uncovering tax records, census records, death records, faculty minutes, and more: anywhere they can find a name.

"I believe they were thinking, 'One day someone is going to say my name. I'm going to be remembered,'" Johnson said.